In the official list of printed works deemed to “harm the national interests of the Republic of Belarus,” foreign authors dominate.

According to PEN Belarus, as of 1 August 2025, at least 80 books by foreign authors are banned in Belarus. In total, 110 titles appeared in the state “stop-list” between November 2024 and May 2025, while another 81 works were added to the list of “extremist materials”. Among those forbidden are works by Anne Applebaum, Hanya Yanagihara, James Baldwin, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen Chbosky, Fredrik Backman, David Mitchell, and Gene Sharp. The authorities fear them because they challenge official dogma with alternative historical memory, moral and political agency, LGBTQ+ and gender diversity, critical thinking, and models of non-violent resistance. Such texts expose the crimes of totalitarianism and give people a language for freedom.

Paradoxically, the bans themselves highlight why these books are so necessary: they open up a “world beyond fear,” where freedom is understood as responsibility and democracy as daily practice – rooted in participation, accountability, and respect for human dignity. Across genres and perspectives, they teach readers to doubt, check facts, distinguish argument from slogan, and grasp the costs of decisions – in short, to think critically. These books nurture a moral imagination and a vocabulary of rights, showing that justice is not an abstract ideal but concrete institutions, procedures, and civic courage. They equip readers with the words to name evil, and the tools to resist it – from solidarity and mutual aid to non-violent action. They inspire: offering examples of human resilience, encouraging people to turn pain into collective action, and awakening an inner moral compass that refuses to accept injustice as “normal” and dares to defend freedom.

The stop-lists include works already part of global conversations about human rights, political regimes, and – to repeat the key words – human pain and dignity. But in Belarus, such writing becomes a criminal matter, exposing the gulf between the repressive system and the language of freedom spoken elsewhere.

The majority of these banned works are not political manifestos but powerful explorations of personal experience, psychological trauma, gender identity, sexuality, adolescence, family violence, and social taboos. Such literature allows individuals to understand themselves, overcome shame and fear, and process hidden traumas. It is a literature of personal emancipation, teaching that human dignity outweighs collective silence. A state sustained by obedience and silence regards self-knowledge as “anti-state activity.” Once people begin naming their feelings, desires, pain, and memories, they become harder to silence, harder to force into conformity.

And what of the overtly political works?

Gene Sharp’s essay From Dictatorship to Democracy was banned as an “instruction manual for revolt”. Yet in reality, it is a sober analysis of the mechanisms of power and the principles of non-violent resistance. In a country where the very idea of resistance is criminalised, such texts are automatically branded “extremist”.

The list of literature deemed “harmful to national security” also includes historical studies: Anne Applebaum’s Gulag or the wartime memoirs of Rommel and Manstein. They shatter the mythical narrative of “heroic” history that leaves no space for doubt, complexity, or criticism of totalitarianism. Their prohibition is an attempt to restore an information iron curtain, cutting society off from more honest, painful perspectives on the past.

A particular wound is the banning of novels that speak to the inner human condition. Fredrik Backman’s Bear Town and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life are global bestsellers about shame, trauma, acceptance, violence, and love. Why are they dangerous to Ł ukašenka’s bureaucrats? Because they evoke empathy and compel readers to understand others – dissolving the fear of difference.

Despite differences of genre, theme, and geography, these banned books share one trait: they challenge the state’s claim to absolute truth. They sketch alternative models of life, morality, and justice. They place no boundaries on love and speak directly to the reader. And that is what makes them dangerous. True literature listens to life in its deepest, most fragile tones – but it does not obey the regime’s commands. It is no servant of power. And for a dictatorship, that makes it the greatest enemy of all.

Voices of books

Below are selected voices of banned books (an author’s selection; the complete list is available on our website)

![]()

«Gulag»

Anne Applebaum

New York: Doubleday, 2003

Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 2004

Date of ban: 24.01.2025 (the list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I recount the history of the Soviet system of forced labour camps: from its origins under Lenin to its demise in the 1980s, through mass arrests, repression, and the lives of prisoners in inhumane conditions. Within my pages are documents, testimonies, archives, and literary sources that expose the scale and mechanisms of the totalitarian machine of violence. I was banned for openly revealing the crimes of Soviet power, for drawing parallels with present-day repressions, and for my dangerous call not to forget the truth about the camp system – a mirror of the totalitarian past from which today’s regime has never distanced itself.

![]()

«Björnstad (Beartown)»

Fredrik Backman

Stockholm: Piratförlaget, 2016

Date of ban: 01.04.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a story about the murder of the soul through bullying. About how hatred is taught to those who refuse to remain silent. I was banned because I showed that violence is not only the work of the perpetrator, but also of those who stand by and say nothing. In Belarus, thousands are hounded for their language, their flag, even for a “like”. Just as in my pages, aggression has become the norm, cruelty justified as “patriotism” or “state interest”. I am destroyed because I expose the psychology of fear – and wherever fear rules, harsh censorship follows.

![]()

«A Little Life»

Hanya Yanagihara

New York: Doubleday, 2015

Kirkus Prize for Fiction

Date of ban: 24.01.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a wound from which compassion begins, a novel about the abyss of human suffering. I tell of traumas that strike into the depths of silence, of shame, despair, and love that demands nothing in return. People read me to understand those living at the limits of endurance. But I was banned in Belarus: I revealed themes the regime does not want to see in schools, in families, or in life itself. For power does not want people, only functions; not trauma, but “happiness by instruction.” I became a mirror of pain – and in it, the censors saw hearts learning compassion and learning solidarity.

![]()

«Goodbye to Berlin»

Christopher Isherwood

London: Hogarth Press, 1939

Date of ban: 01.04.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a novel about an age when people did not yet realise their world was about to vanish. From the Weimar Republic to the rise of Nazism, I tell of freedom – whose profound value is often unrecognised until it is lost. I was banned because my pages are a document of free life on the edge of catastrophe. I warn: the beautiful, polyphonic, open world can still be strangled by dictatorship.

![]()

«The secret history»

Donna Tartt

Date of ban: 04.08.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

“The Secret History” is Donna Tartt’s debut novel, telling the story of a group of students at an elite college in New England. The main character, Richard Papen, is drawn into a mysterious circle of friends who study under the guidance of an eccentric professor. Together with them, he uncovers dark secrets that lead to tragic events. The novel explores themes of betrayal, murder, and morality, showing how far people are willing to go in the name of their obsessions. “The Secret History” is a gripping tale about forbidden knowledge and the consequences that come with possessing such secrets. A must-read for fans of psychological literature and thrillers.

![]()

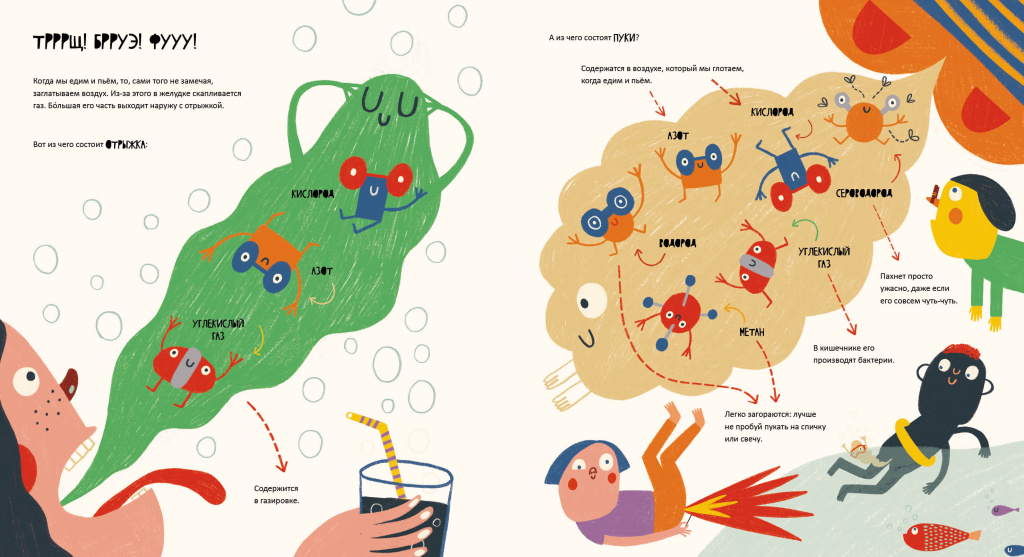

«The Secret Life of Farts and Burps»

Mariona Tolosa Sisteré

Date of ban: 30.09.2025 (the list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

The book The Secret Life of Farts and Burps by Mariona Tolosa Sisteré is a fascinating presenta

tion of what happens in our bodies when we digest food. Why do people and animals fart? How is digestion organized and should you eat so as not to harm your body?

![]()

«The Wasp Factory»

Iain Banks

London: Macmillan, 1984

Date of ban: 29.05.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a work ranked by critics among the 100 Best Novels of the 20th Century. A literary experiment that breaks the boundaries of norms. I am banned because I deny the reader comfort. I depict the complexities of the human psyche in concentrated form. I show the social monster in its most unattractive aspects. The current regime in Belarus does not tolerate such truth, as it can recognise itself in it. And so, for its servants, it is more convenient if I do not exist.

![]()

«Lullaby»

Chuck Palahniuk

New York: Doubleday, 2002

Date of ban: 24.01.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a warning novel about how power over the fate of others can destroy a person – and how a careless word can kill or break a life. If the crime leaves no trace, will you commit it? Temptation and choice at once. In Belarus today, my story is more than relevant. I was banned because I revealed the mechanisms of manipulation and violence. In other words, I hold up a mirror to the practices of the regime’s own servants.

![]()

«They Both Die at the End»

Adam Silvera

New York: HarperTeen, 2017

Date of ban: 21.11.2024 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am a confession where love is stronger than fear. Even at the threshold of death, it is possible to live a whole life in a single day. Brief as it is, that day can transform an entire inner world. I teach reflection on mortality not through guilt or division, but through intimacy and meaning. The regime fears me because I bring to Belarus another vision of humanity – one that defies their “traditional morality”.

![]()

«My Dark Vanessa»

Kate Elizabeth Russell

New York: William Morrow, 2020

Date of ban: 21.11.2024 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Голас кнігі:

Я – тая, што з’явілася праз 70 гадоў пасля выхаду набокаўскай «Лаліты». Ува мне нарэшце прагучаў не толькі голас другога боку, але і праблема двухбаковай улады ў адносінах. Я расказваю пра траўму, якую доўгі час адмаўляюць. Мяне забаранілі ў Беларусі, бо ю разбураю звыклую схему «вінаватых і правых», бо прымушаю слухаць і сумнявацца, падтрымліваю тых, хто пацярпеў. Я небяспечная, бо паказваю, што права голасу ўрэшце атрымаюць і тыя, хто занадта доўга змушана маўчалі.

![]()

«Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters»

Peter Langman

New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009

Date of ban: 24.01.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am psychology, not justification. I seek to understand what drives children to violence. I was banned because I do not fit into absolute schemes of “evil,” but dismantle them – opening space for reflection, dialogue, and prevention. In Belarus today, tragedy is addressed only through punishment. I show instead that such an approach deepens the problem, and that the solution lies in seeking understanding.

![]()

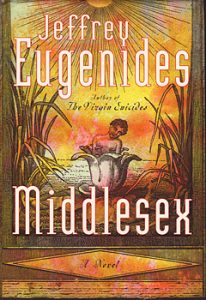

«Middlesex»

Jeffrey Eugenides

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002

In 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

Date of ban: 29.05.2025 (list of publications deemed “harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”)

Voice of the Book: I am an epic that won my author the Pulitzer Prize. Not only for confronting the subject of hermaphroditism, but for much more: I am about identity that refuses to be trapped in polarities. I was banned because I share human experiences without aggression or judgment. I am the literature of a new ethic, a new world. And that frightens those in Belarus who wish to enforce only one “correct” image of the traditional person.

![]()