As early as the first half of the nineteenth century, a war was launched against the Uniate book – the legacy of the Union of Brest, which in the late sixteenth century had united a significant part of Belarusian and Ukrainian Catholics and Orthodox believers into a separate Greek-Catholic (Uniate) Church. For several centuries, this was the principal Belarusian confession, with its own rich written tradition. It was this tradition that the Tsarist authorities deliberately eradicated, as described in detail by Uładzimir Arłoŭ in his Secrets of Połack History. He shows how, in the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire unfolded a systemic campaign to annihilate the Uniate tradition, Belarusian culture and language: parishes were liquidated, priests and parishioners were forcibly converted to Orthodoxy, books, archives and libraries were confiscated and destroyed, and local communities were stripped of fundamental rights through conscription and serfdom. All of this was accompanied by targeted Russification, designed to turn Belarusians into “a part of Russia” by depriving them of their own history and cultural memory.

A significant milestone came with the circular of the Main Directorate of Censorship of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs of 30 April 1859, which prohibited the publication of Ukrainian literature “for the people” in the Latin alphabet. This applied equally to the Belarusian language. On this basis, the censor banned the publication of Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz in the Belarusian translation by Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič.

The prohibition of Dunin-Marcinkievič’s texts appears particularly strange and offensive. Today, not only his works but even modern forewords and commentaries to them fall under attack. How could the writings of a nineteenth-century author threaten today’s Belarus? By affirming the Belarusian agency and its distinctiveness from Russia. Continuing the traditions of the Russian Empire, today’s Belarusian authorities are erasing what once shaped Belarusian identity through literary form.

This carries both horror and recognition. For within those texts, written in an as-yet unformed language still feeling its way, something vital endures: the origins. And with it comes a fear of history itself, of the simple fact that Belarusians existed long before the Soviets, before Central Committees and ministries, before presidential administrations – and even before the president himself.

Thus, the persecution of Belarusian books did not begin in 2020, nor in 1994, nor even in Soviet times. It stretches back to the nineteenth century, born of fear of history, language, and identity. And yet today, in 2025, despite bans, obstacles, and difficulties, the Belarusian book breaks through like grass through asphalt, almost always against the grain of the state. This alone is powerful testimony: the Belarusian voice was, is, and will remain. It can be heard even through the concrete of censorship – even through the fear of criminal prosecution for reading, keeping, or sharing “extremism”.

Voices of books

Below are selected voices of banned books (an author’s selection; the complete list is available on our website)

![]()

«The Winds Flow…»

Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič

(from Selected Works)

Minsk: Belarusian Science, 2019

Date of ban: 15.08.2023 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am a poem written on the eve of an uprising, attributed to Dunin-Marcinkievič. I breathe with the freedom of the Latin script and the anger of Warsaw in 1861, when Russian occupiers met an unarmed patriotic demonstration with bullets. The author witnessed how people marched for liberty and their homeland with prayer on their lips. The exact number of victims remains unknown, kept secret. I was banned 160 years later for bearing witness to that time: truth does not die; it returns. I am a link between generations of the unbroken, which is why they try to silence me – now under the label of so-called “extremism”.

![]()

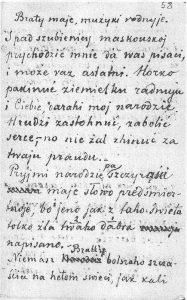

«Letters from Beneath the Gallows»

Kastuś Kalinoŭski

These letters were written and sent by Kastus Kalinoŭski during his trial before his execution by hanging in March 1864.

Voice of the Book: I am the final words of a fighter, the leader of the anti-Russian uprising, before his death. Here they are: “For I tell you from beneath the gallows, my people, that you will only live happily when there is no longer a Muscovite above you.”

The letters called on the people not to remain silent. For this, I was once censored by the Russian Empire, and now the Łukašenka regime continues the practice. It despises my appeal to Belarusians: do not be cattle! It senses that my words are stronger than the batons of riot police.

![]()

«Buračok’s Belarusian Stories»

Francišak Bahuševič

Voice of the Book: I am a work in the native tongue, yet I never reached the printing press. Prepared for publication in 1899, I was blocked by Tsarist censorship. They hid the manuscript from Belarusians so thoroughly that it was eventually lost altogether. The same fate befell Bahuševič’s third planned collection, The Belarusian Violin, which was to appear posthumously but never did. I always spoke in the voice of ordinary people about their harsh lives. I shattered the illusion of a fictitious existence – and for that, I was banned.

![]()

«The Belarusian Violin»

Ciotka (Ałaiza Paškievič)

Voice of the Book: I am a collection that resounded in Vilnius when my rebellious author first found her voice. She drew on the traditions of her celebrated predecessor, Frantsishak Bahushevich, and it was no accident that she named me after one of his banned books. But Ciotka went further: her poetry was revolutionary, her verses a complete rejection of Tsarist autocracy. The empire banned me because I became an explosive voice of my time. My author was not a convenient muse, but a symbol of resistance and revolution. And today, for the same reason, they do not want me to be heard.

![]()

«The Little Flute (Žalejka)»

Janka Kupała

Voice of the Book: I am a Belarusian, though I was born in the imperial capital. A poem and ninety-seven verses, among them the programme text for all Belarusian literature: “And who is going there?”. For years, it served as the unofficial national anthem, translated into eighty-two languages worldwide. It is no accident that the Tsarist authorities twice confiscated the collection. Yet my flute did not fall silent. I sound still. I exist – and I always will.

![]()