Within just a few years, Belarus has witnessed the seemingly unthinkable: literary classics officially branded as “criminals”. Their books are banned, their names erased from libraries, curricula, and bookshops. Their words have been declared dangerous.

Why? Because each of these writers called on their readers to defend Belarus, to speak out, and not to surrender. This alone is deemed a crime by a government that fears the voice of conscience. For a dictatorship, a classic is not simply an author but a moral compass. And when that compass directs people towards truth rather than submission to “statehood”, the regime seeks to obliterate it.

The banning of deceased authors is a profound act of disrespect – a shot fired at collective memory, an attempt to tear the past from people’s hearts and replace it with emptiness. By doing so, the authorities imply: “You are orphans. Your only father is the one who sits on the throne.”

Those who persecute writers of the 21st century simultaneously seek to rewrite the 20th. Figures who symbolise Belarusian national identity have been placed under ban: Hienijuš, who, stripped unlawfully of Czechoslovak citizenship, never accepted Soviet citizenship until her death; Arsieńnieva, forced into exile after the Second World War, whose poetry resonated from abroad; Łastoŭski, historian, politician, and victim of Stalinism; Pietraškievič, playwright, prose writer, and encyclopaedist. They are listed not for “extremism”, but for their Belarusian identity, which jars with today’s ideological agenda.

During Stalin’s rule, many of these authors had already endured censorship. In his book Behind the Zealous Work of the Chekists (based on archival documents), Alaksandr Łukašuk examines the mechanisms of NKVD censorship. On 3 June 1937, Glavlit of the BSSR issued Order No. 33, entitled “List of Literature to Be Confiscated from Public Libraries, Educational Institutions and the Book Trade”. This decree was extensive: the list of “harmful books” filled 111 pages. The alphabetical register of books published in Belarus included 421 titles. Against 53 author names, it simply read “all works” – meaning that many more books were to be destroyed, literally burnt. Among the targeted authors were Maksim Harecki, Francišak Alachnovič, Janka Kupała, and many others. Some were executed, others became classics despite torture, their works later entering Soviet school textbooks, while still others died under mysterious circumstances.

We cannot forget the “Night of the Executed Poets”, one of the consequences of that decree. On the night of 29–30 October 1937, more than 100 representatives of the Belarusian intellectual elite – cultural, artistic, and scientific figures – were executed in the cellars of Minsk’s NKVD prison known as “Amerikanka”. It was only one of the most infamous massacres; executions took place elsewhere and at other times. And those executed were not so much “anti-Soviet”, as “pro-Belarusian”, their “crime” being their commitment to the Belarusian language and culture – something fundamentally incompatible with Soviet ideology, deeply rooted in Russian culture.

The rhetorical question remains: how can a nation develop when its most active and talented cultural and intellectual figures are destroyed? That was precisely the aim: to kill, to erase, to pretend that nothing ever existed.

Today’s regime continues the war both against those who were repressed and forgotten under Soviet rule and against those who survived and became part of the Soviet literary canon. By banning the books of those authors, today’s authorities perpetuate the traditions of Stalinism, seeking to annihilate the legacy of earlier generations of Belarusian writers – those who built and fortified the nation, its community, and its society.

Two awards of PEN Belarus are named in honour of these “banned” writers:

- The Natalla Arsieńnieva Poetry Prize

[Go to Natalla Arsieńnieva Poetry Prize landing page]

[Read about Natalla Arsieńnieva]

- The Francišak Alachnovič Prize for Literature Written in Prison

[Go to Francišak Alachnovič Prize]

Voices of books

Below are selected voices of banned books (an author’s selection; the complete list is available on our website)

![]()

«In the Clutches of the GPU / Siedem lat w szponach G.P.U. / The Truth about the Soviets»

Francišak Alachnovič (1888–1944, killed)

Date of ban: Order No. 33 of the BSSR Glavlit, 3 June 1937. Alachnovič was listed second out of 421 entries, marked: “All books”.

Francišak Alachnovič, known as the “father of Belarusian theatre”, was a playwright, theatre scholar, actor, director, and publicist. He was one of the first in world literature to describe the horrors of Soviet repression and torture in Bolshevik labour camps. He had been arrested under the Russian Empire, under Poland, and under the USSR. Accused by the Soviets of “espionage for Poland”, he was exchanged for the linguist and politician Branisłaŭ Taraškievič, who was later executed during the “Night of the Executed Poets”. Alachnovič was killed in Vilnius.

Voice of the Book: I am one of the first testimonies in world literature about Soviet repression and torture. I was first published in Polish in 1934, and only in 1937 in Belarusian. Did the world hear me? My protagonist is a trusting Belarusian who returned home from abroad, deceived by Soviet propaganda, hoping to realise his dream of building a Belarusian theatre. Instead, he was thrown into a camp and tortured. Today, in Ł ukašenka’s Belarus, so-called “return commissions” also entice Belarusians to come back. Those who believe them risk sharing my hero’s fate.

![]()

«Two Souls»

Maksim Harecki (1893–1938, executed)

Date of ban: Order No. 33 of the BSSR Glavlit, 3 June 1937. Haretski was number 83 on the list of 421 entries, marked: “All books”.

Maksim Harecki was one of the founders of Belarusian national prose and made a significant contribution to the development of Belarusian culture and the formation of national identity. His works were silenced for decades.

Voice of the Book: I am a novella that bears witness to the split in Belarusian identity between East and West, and the difficulty of choice and self-determination. In Soviet times, I dared to speak of the cynical cruelty and inhumanity of both the Tsarist Empire and the Bolsheviks. This was inconvenient for the Soviet authorities and contradicted their ideology. I raised one of the fundamental questions of Belarusian identity, refusing to conform to the one-dimensional values promoted by the USSR. I showed the struggle between two souls – imperial and national – and what the empire does to the human being. Today, the empire continues to strangle Belarus with its “Russian World”.

![]()

«Selected Works»

Lidzija Arabiej (1925–2015)

Minsk: Knihazbor, 2013

Date of ban: 15.08.2023 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am the voice of a representative of the older generation of Belarusian Soviet writers. The seventieth volume of the legendary book series Biełaruski Knihazbor (Belarusian Library). Within my pages lies the documentary story I Become Song, dedicated to the persecuted poetess Ałaiza Paškievič (Ciotka), one of the classics of Belarusian poetry at the start of the 20th century. I was banned because I embody literature of human dignity – something unwanted where obedience is demanded of people, and the silence of books.

![]()

«Selected Works»

Natalla Arsieńnieva (1903–1997)

Minsk: Biełaruski Knihazbor, 2002

Date of ban: 15.08.2023 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am the book of a poet who, while still young, was forced into lifelong exile, though she continued to pray for Belarus. My author penned the iconic hymn Mahutny Boža (“Almighty God”), which became one of the symbols of the 2020 protests. My poems, librettos, and memoirs are a dream of a free, European, non-Soviet homeland. My Belarus is a sacred inheritance of the people – intolerable for a regime that tramples national feeling. I was banned because I am hope and faith for today’s generation of Belarusian political émigrés.

![]()

«Selected Works»

Vacłaŭ Łastoŭski (1883–1938, executed)

Minsk: Biełaruski Knihazbor, 1997

Date of ban: Order No. 33 of the BSSR Glavlit, 3 June 1937 (No. 201 on the list of 421 entries).

Later: 30.04.2024 and 14.10.2024 (National List of Extremist Materials).

Voice of the Book: I am the voice of a man who sought to build a Belarusian state a hundred years ago. My author was extraordinary: a writer, academic of the Belarusian Academy of Sciences, and Prime Minister of the Belarusian People’s Republic. His Short History of Belarus was the first book to argue for the Belarusian character of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Past and present authorities alike reject my truth: that the history of Belarusian independence began long ago, not yesterday and not through the will of others. Therefore, Belarus lives forever!

![]()

«Selected Works»

Aleś Pietraškievič

Minsk: Belarusian Science, 2017

Date of ban: 30.04.2024 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am the work of an author who managed to preserve spirituality even while working within the Communist Party leadership under totalitarianism. I was banned because, in the eyes of today’s officials, I am “too” human. I do not preach, propagandise, or accuse, but speak with pain and love – about bleak Soviet everyday life and about national geniuses, fighters for freedom and dignity. I am written without official pomp, but with a conscience that provokes doubt. And doubt is the enemy of any totalitarian system.

![]()

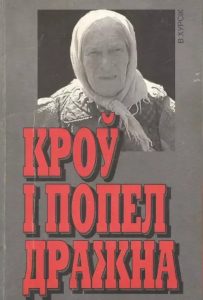

«Blood and Ashes of Dražna: Stories of a Partisan Crime»

Viktar Chursik

Minsk: V. Chursik, 2003

Date of ban: 06.03.2025 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am a book that reopens wounds. On 14 April 1943, partisans attacked the village of Dražna, shooting indiscriminately, slashing, and burning innocent villagers alive. Those who killed their own compatriots were later celebrated as heroes. This tragedy was even more terrible than Khatyn, which the Nazis burned. I was banned because I shattered the conventional narrative of partisan heroism. Yet people must not fear the truth – we have the historical right to genuine, not airbrushed, memory.

![]()

«National and Cultural Life in Belarus During the War (1941–1944)»

Leanid Łyč

Vilnius: Naša budučynia, 2011

Date of ban: 09.01.2023 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am a study that dismantles clichéd narratives of the war. Contrary to false histories, I demonstrate that, compared with Stalinist terror and Russification of the 1930s, there were attempts at a revival of language, church, and culture under German occupation. In the eyes of official ideology, this is outrageous, for it does not fit into Soviet or today’s ideological constructs. That is why they try to silence me – along with the history that does not fit the textbook of “victors”.

![]()

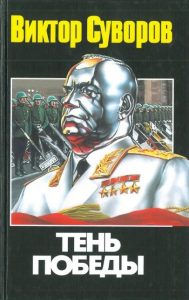

«The Shadow of Victory»

Viktor Suvorov

Donetsk: Stalker, 2003

Date of ban: 09.01.2023 (National List of Extremist Materials)

Voice of the Book: I am a book that dares to challenge sacred myths. For instance, I argue that the cost of victory could have been different. I claim that Stalin not only failed to save Europe but also actively prepared his own offensive against it. I was banned because I strip away the glossy mask of Soviet military mythology. I insist that a nation cannot live forever on pompous parades, and I raise the question of historical responsibility as well as heroism. For this, I am deemed dangerous.

![]()