The cost of free speech in Belarus: €350 for reading and eight years for writing

An author’s reportage from the exhibition of banned books

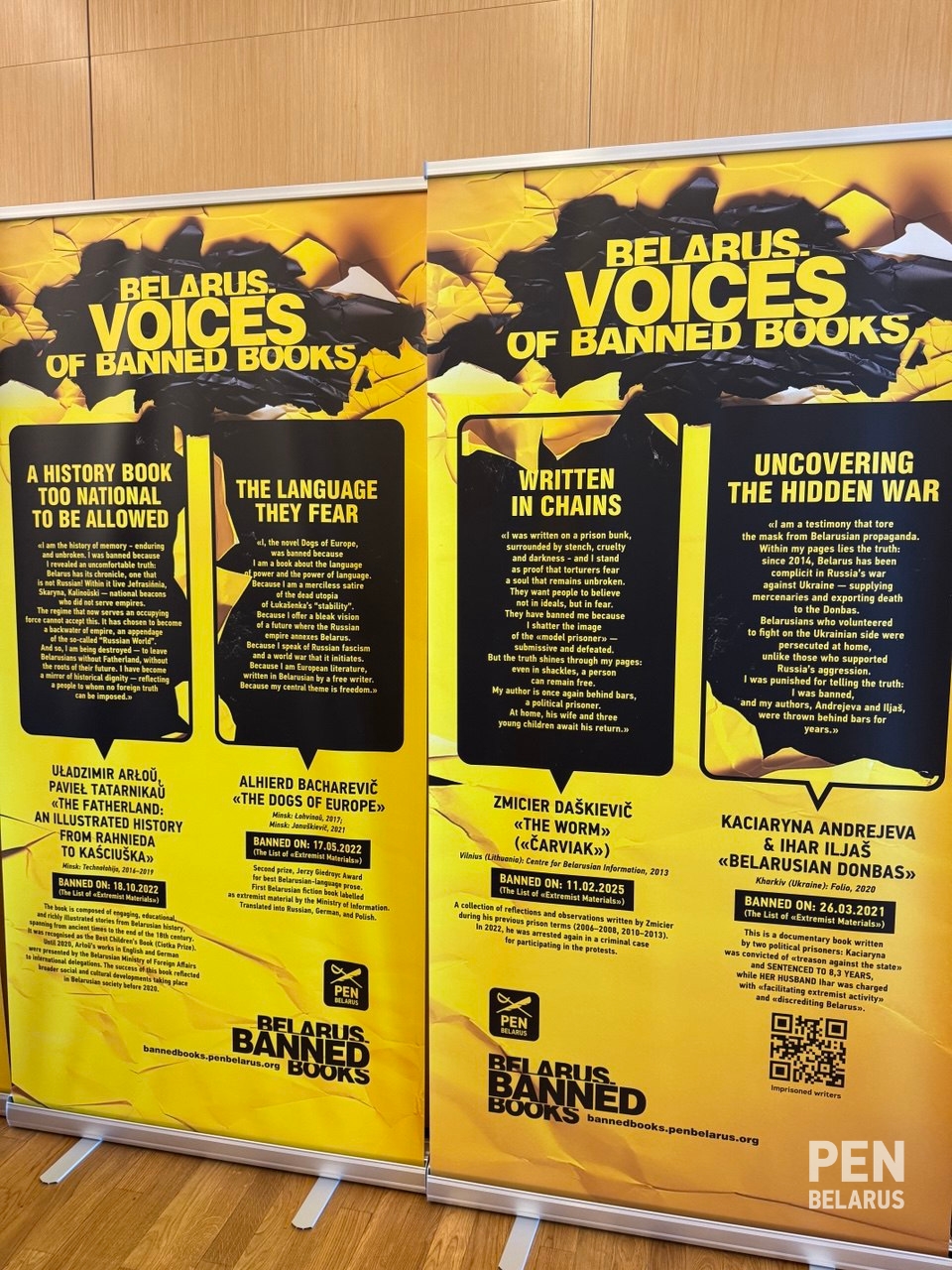

If a book is, among other things, a vessel of symbols, then a book exhibition turns into a magnifying glass that enlarges everything the censors would rather keep invisible. So, what did visitors at the European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk discover when confronted with a visual project devoted to literature banned by the Belarusian authorities? And how did they read the arresting posters, and the stark, uncompromising information assembled by the PEN Belarus team?

Targets: writers and readers

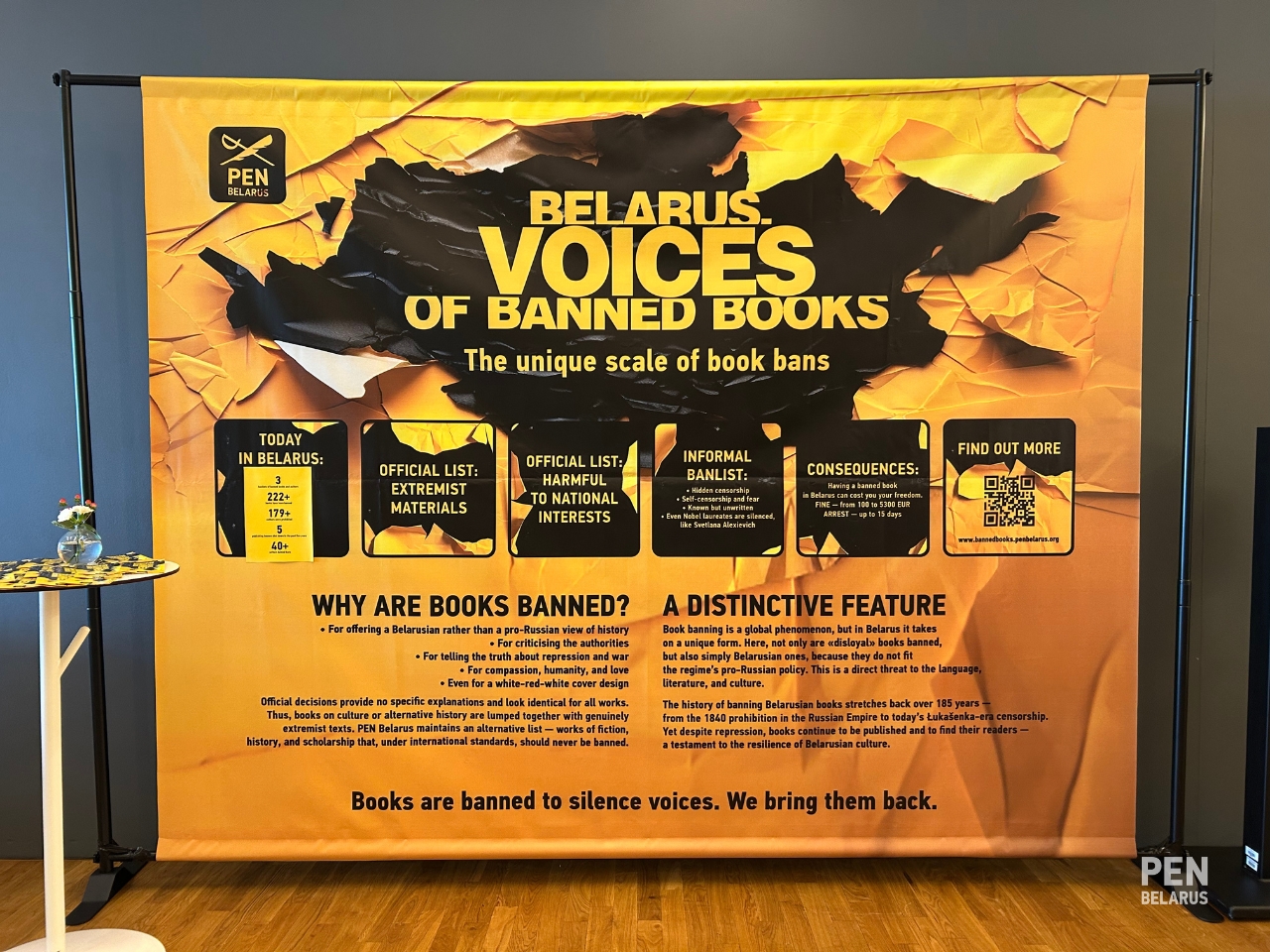

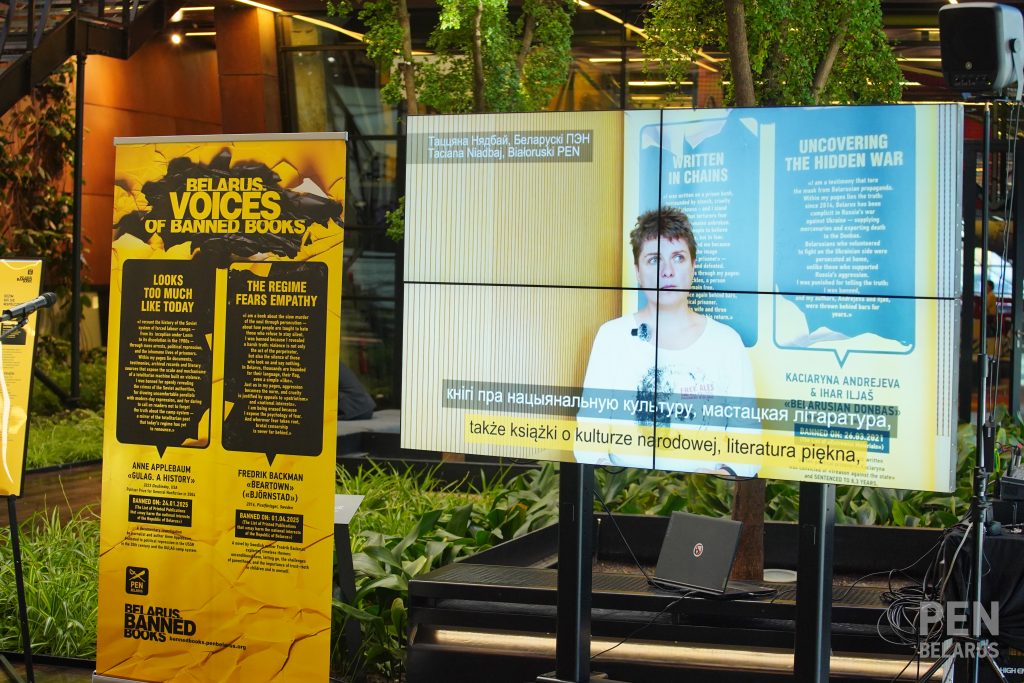

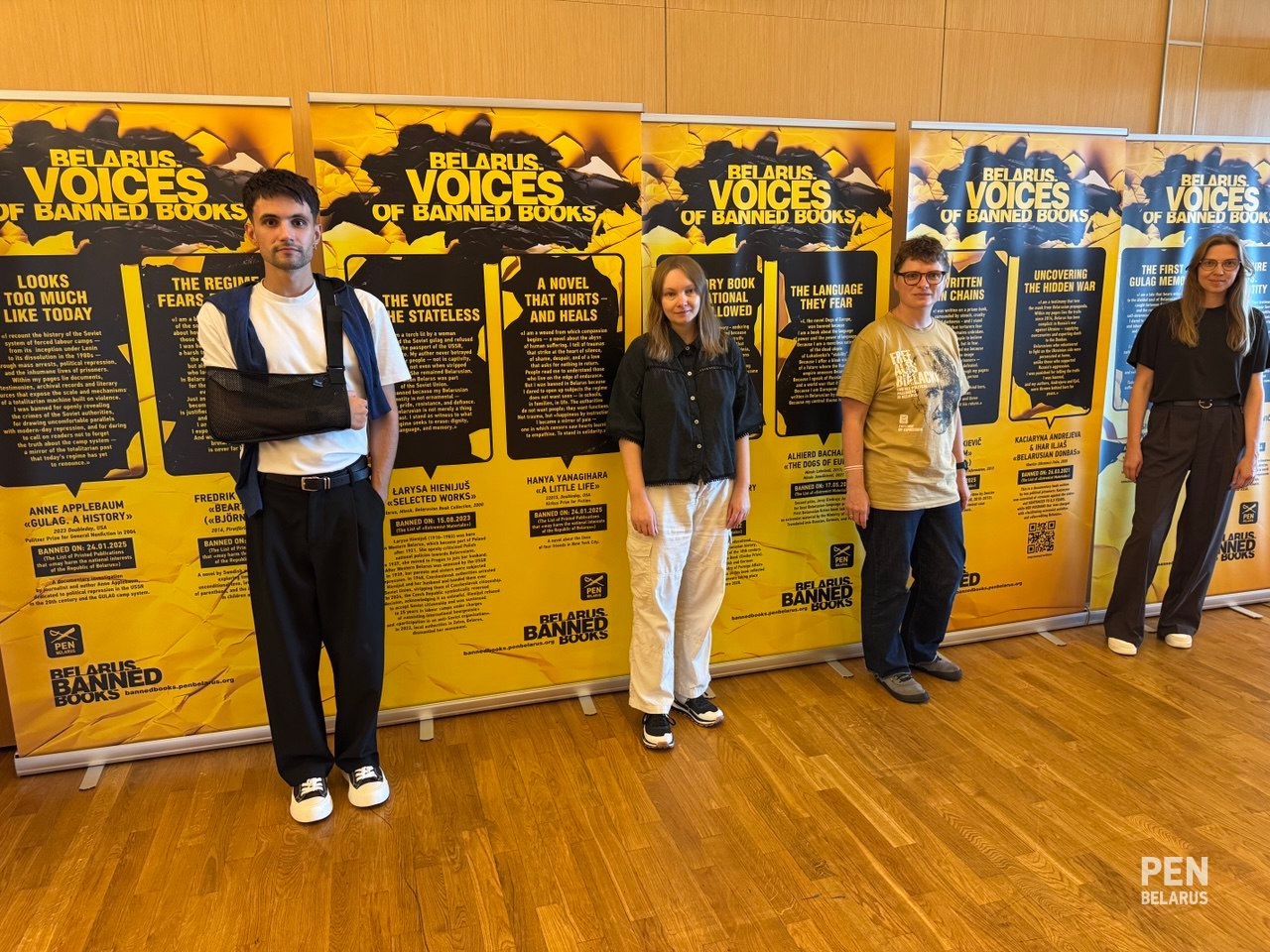

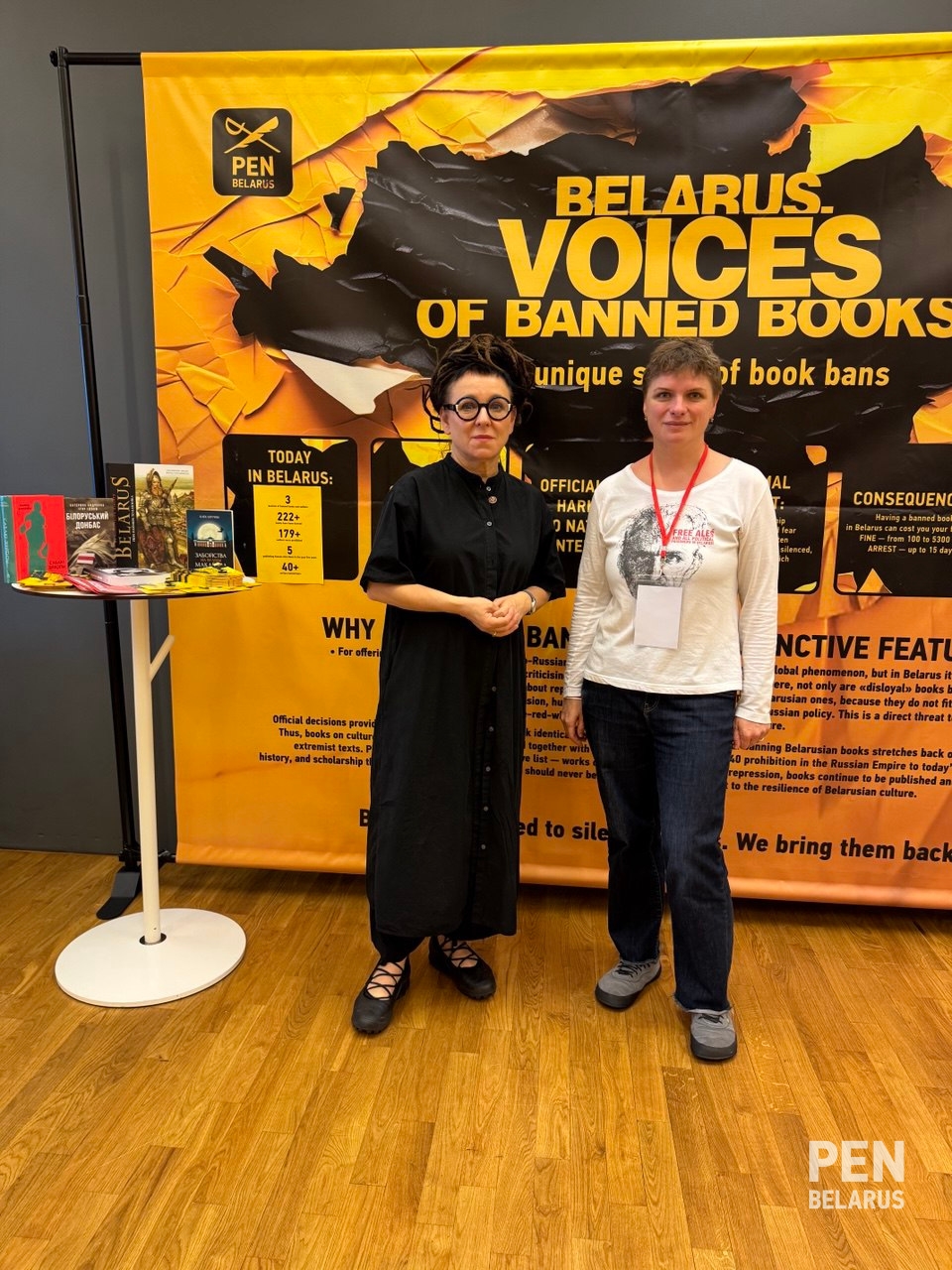

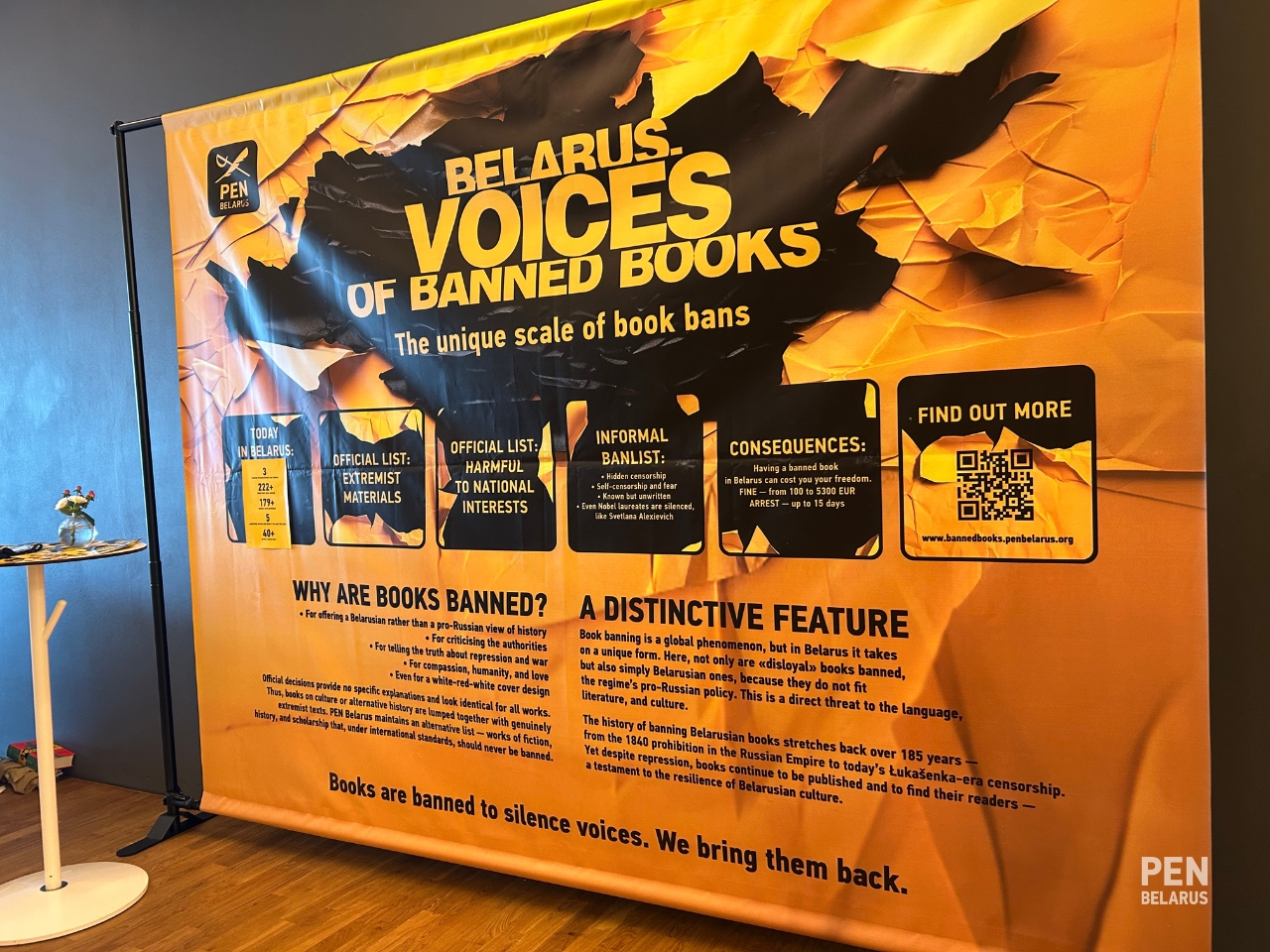

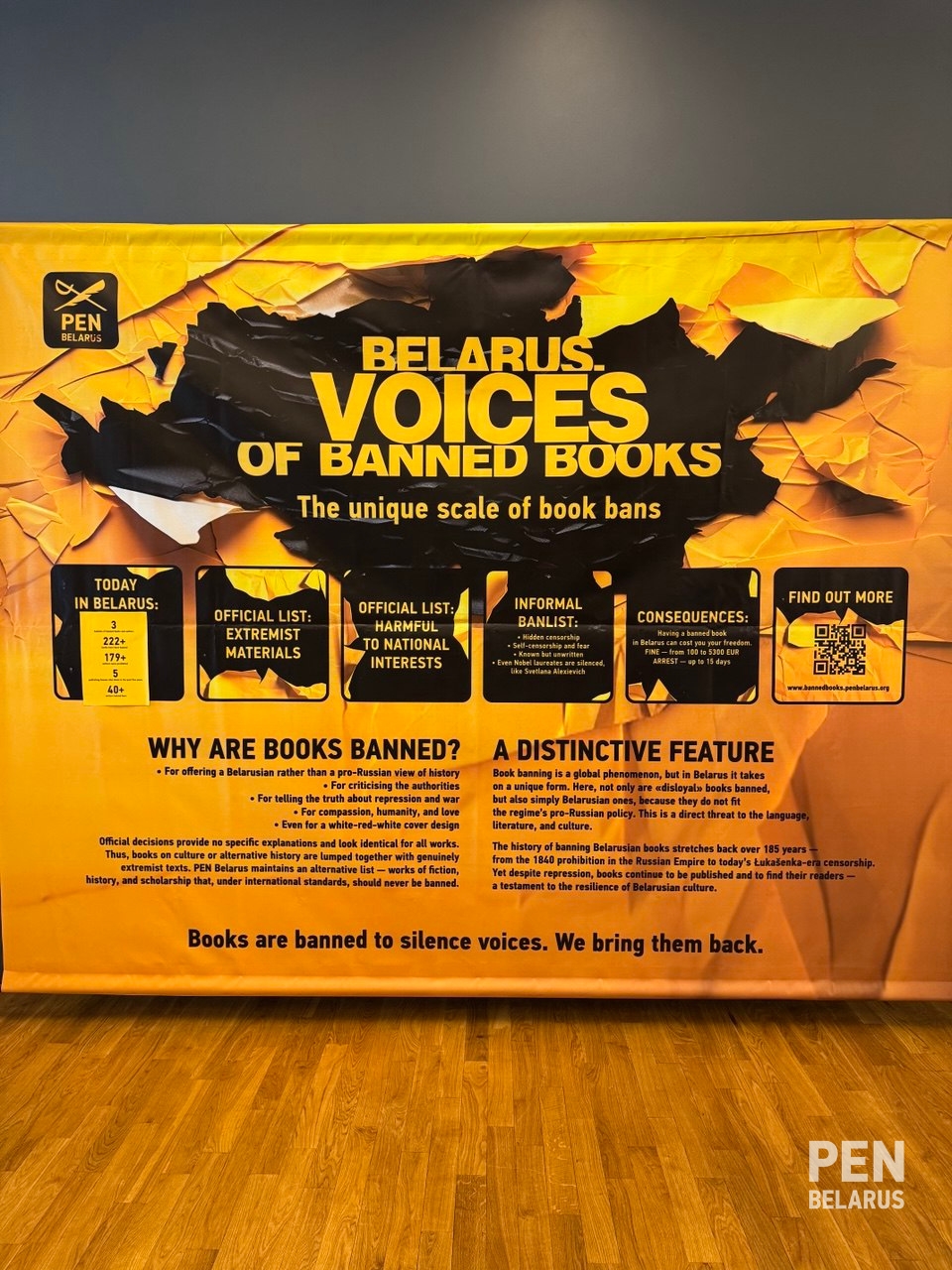

The exhibition had its first outing in early autumn in Kraków, at the 91st PEN International Congress, where it caused a real stir. And no wonder: censorship and the urge to control speech are, sadly, global habits. But set against this wider picture, the Belarusian book purge appears in sharper, more shocking relief. It exposes a gaping cultural and political rift — one that is deepening at alarming speed.

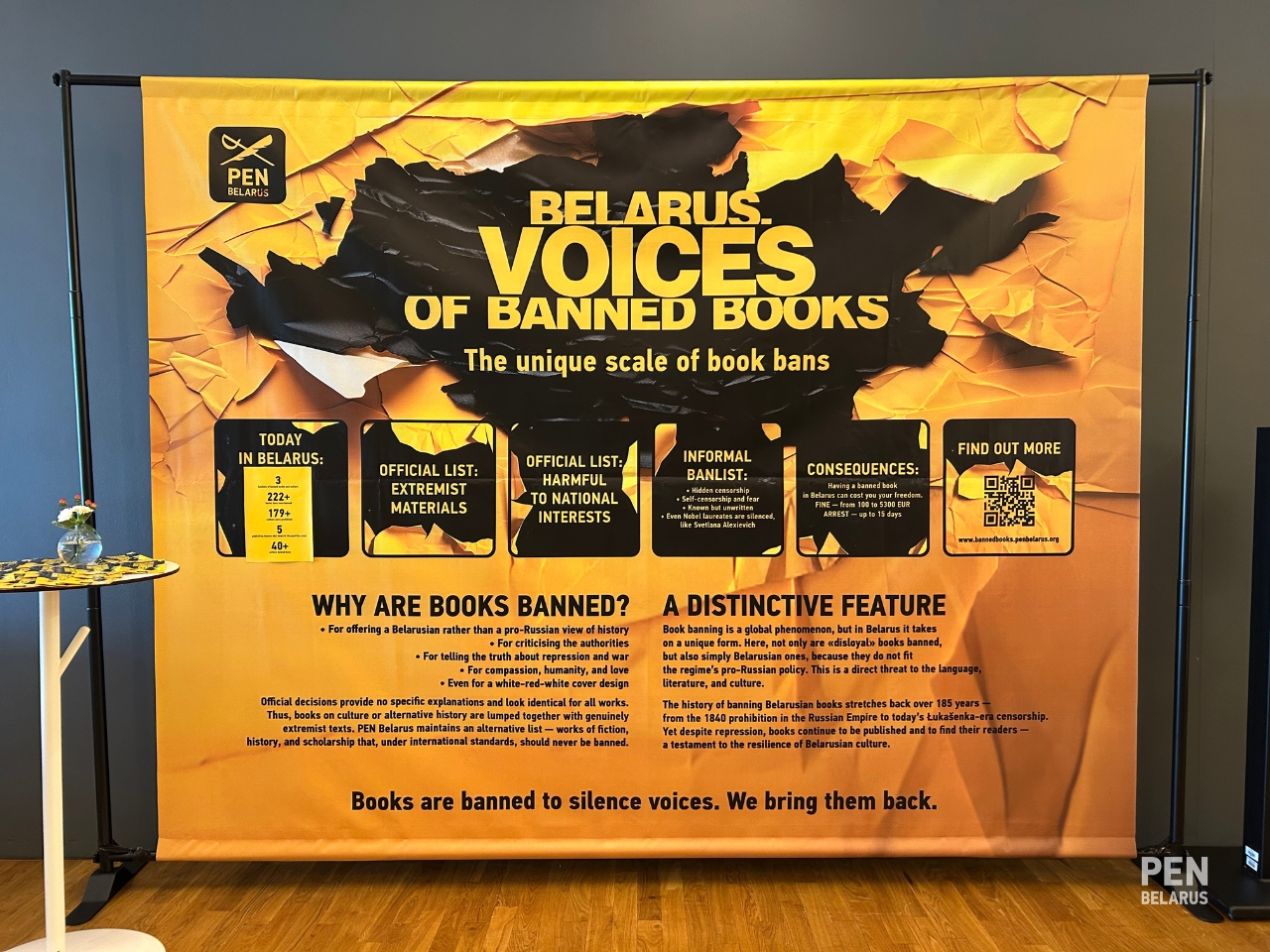

By early September, the list of forbidden titles in Belarus had already included 222 books and 179 authors. By mid-November, those figures climbed to 258 and 208 – a leap of 16.2% and 16.9% in just six weeks.

If only writers’ and readers’ incomes were growing as fast… But no. On the contrary: writers labelled as “extremists” face a wide range of serious sanctions, while readers who take the risk — even accidentally — may face administrative arrest of up to 15 days and a fine of up to 1,260 rubles. This applies even if the decision to ban the book is issued after it has already been purchased.

Visitors stare at the posters, do a quick calculation, and murmur to one another:

“About €350. Heavens… I have five such books at home. That’s the price of a beat-up Ford.”

Such is the going rate for the freedom to read in Belarus today: nearly two-thirds of the average monthly wage.

Volha lingers before the poster devoted to Belarusian Donbas, the book by journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva and her husband, Ihar Iljaš.

“In 2020, I was utterly captivated by Kacia’s reporting from the streets of Minsk. I followed her precisely because I was reading her book at the time. It struck a deep chord — I was born in Ukraine and lived there until Year Five. I know from relatives and friends back home that every detail in that book is true. And for this honesty, eight (!) years in prison. I only hope she and Ihar find the strength to endure such cruelty for telling the truth.”

For the record: under the regime’s own criminal logic, authors of such books may face up to six years of imprisonment. Overall, for her professional activity and the exercise of freedom of expression, Katsiaryna Andreyeva received 8 years and 3 months for allegedly “transferring state secrets of the Republic of Belarus to a foreign state, an international or foreign organisation, or their representative”…

Nearby, Jaŭhien, a former entrepreneur from Viciebsk, offers his reflection:

“This exhibition inspires, above all, respect for the people whose work – based on some archaic, barbaric reasoning – has been branded ‘extremist’, ‘destructive to the state’, or ‘morally harmful’. Their books are treated as dangerous objects that must be banned, guarded, or ideally destroyed – burned in boiler rooms, or pushed by bulldozers into mass graves of paper. My respect to the writers, my solidarity with people of the word. And my gratitude to the organisers of this exhibition.”

We speak with publicist, author and long-time Radio Liberty editor Alaksandr Łukašuk.

– Two books from this year’s Giedroyć Prize shortlist – your own and one by Klok Štučny – have already been labelled “extremist”. Last year’s winner, Valanсin Akudovič’s Sisyphus, has also been blocklisted. Is this a coincidence, or a pattern; a new form of censorship that turns literary achievement into potential criminal evidence? What can we do about it?

“Editing deals with beauty; censorship deals with power. And while any authority indeed has not only the right but sometimes even the duty to forbid what harms human freedom, in Belarus, power bans because it is afraid. It fears for itself. It fears words, and it fears silence. It fears tomorrow and yesterday. It fears language. It fears Giedroyć.

A frightened person cannot write. A person who writes is not scared.

But what the authorities fear most is a person who reads. Writers can be imprisoned or shot. Readers, however, that is the audience the regime truly dreads when it bans books.”

Targets: Belarus and freedom

We speak with Mikałaj Sapieńka, now living in forced political exile in Gdańsk. Asked for his impressions of the exhibition, he replies with a question of his own:

“Given the scale of today’s censorship and repression – would Francysk Skaryna himself pass an ideological review?”

A sharp and telling observation. Indeed, under the current logic, even Skaryna – like Dunin-Marсinkievič, Łarysa Hienijuš, or Maksim Hareсki – could well be “banned”. His writings speak of national dignity and a distinctly European openness, ideas hardly compatible with today’s authoritarian sensitivities.

Mikałaj, formerly an engineer in Brest and now working as a stevedore in the Gdańsk port, continues:

“I’ve just learned that the history of banning Belarusian books stretches back more than 185 years to 1840, when Russian imperial officials first began this practice. And of course, the banning of Baharevič’s Dogs of Europe happened precisely because it imagines Belarus breaking away from ‘Mother Russia’ towards Europe. It’s a direct continuation of Tsarist censorship.”

We read together the book’s own explanation for why it was banned:

“Because I offer a stark vision of a future in which the Russian Empire annexes Belarus.

Because I write about Russian fascism and show the empire starting a new world war.

Because I am European literature written by a free Belarusian author.

Because my central theme is freedom.”

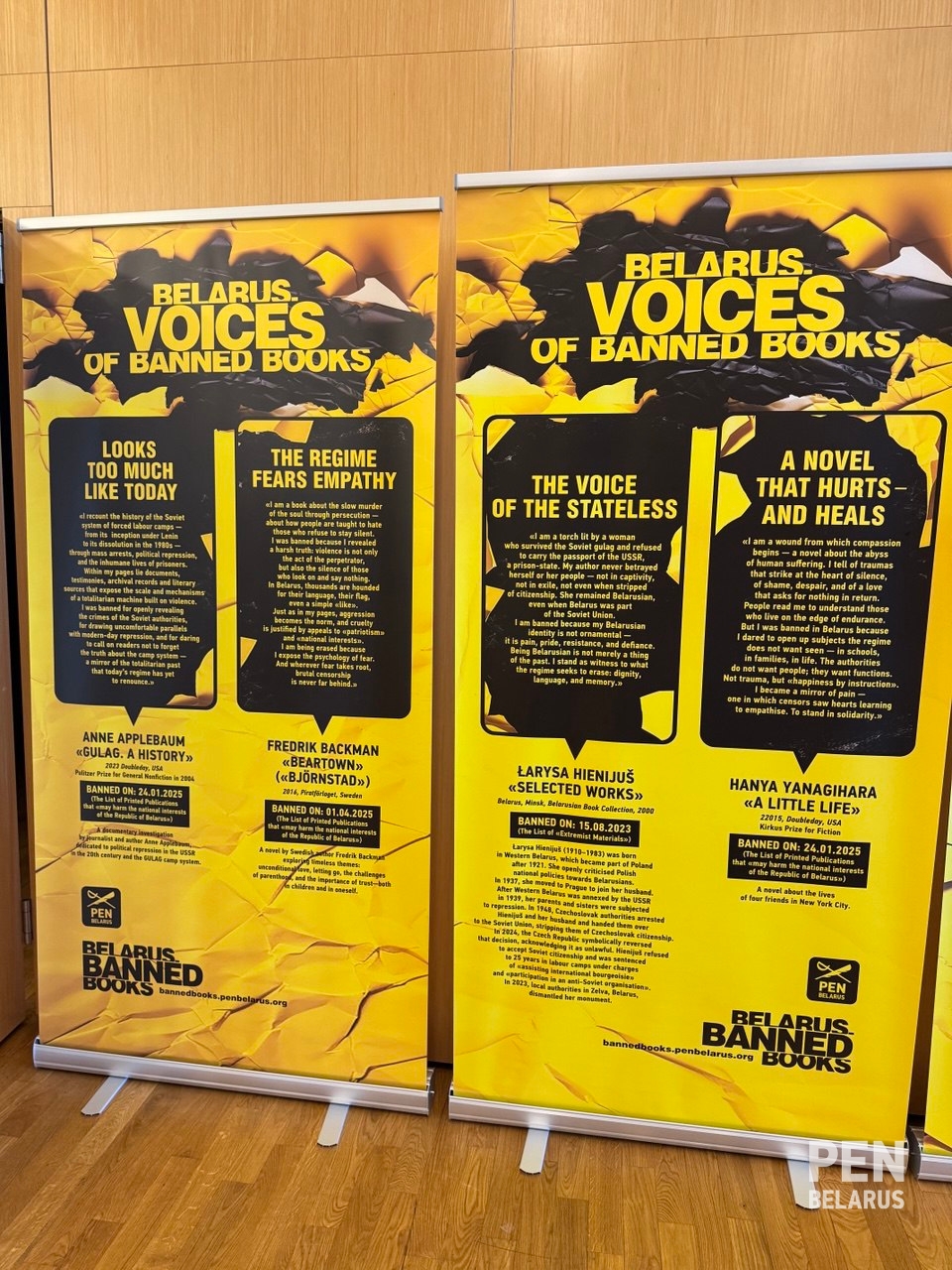

Visitors especially appreciate the creative decision to let the banned books “speak” for themselves. The visual concept – executed with striking precision by the exhibition’s designer – earns high praise from the public.

Political analyst Alaksandr Kłaskoŭski of the Pozirk news agency and the laureate of the Freedom Generation’s Voice Award offers his reflection:

“The Belarusian authorities maintain two ban-lists: so-called ‘extremist’ publications and those deemed capable of ‘harming national interests’. Both labels are pure hypocrisy. What we are witnessing is political persecution, plain and simple.

Works by Pavieł Sieviaryniec, Uładzimir Niaklajeŭ, Łarysa Hienijuš – people who never bent the knee – are targeted precisely for that reason.

The absurdity reaches comic levels: Łukašenka laments that no one can formulate a national idea, yet his officials have banned a book titled The Belarusian National Idea. Clearly, its contents do not fit the Procrustean bed of Łukašenka’s worldview.

The authorities want a monopoly on interpreting history. That’s why they suppress books exposing NKVD executions in Kurapaty or the works of Uładzimir Arłoŭ.

Put bluntly, the regime’s gatekeepers operate on a mix of obscurantism and sheer stupidity. And in the age of the internet, these bans are meaningless. Free words still find their readers.”

Targets: history and the present

More visitors drift into the discussion. Polish IT specialists Łukasz and Magdalena, who work closely with Belarusian colleagues, pause in front of a poster.

“We’re trying to make sense of this one: Hanya Yanagihara. How could A Little Life possibly be dangerous? A novel about shame, love, trauma, and the struggle to accept oneself – it became a global bestseller. Poland adores it. And yet in Belarus it’s banned…”

It’s a reaction heard throughout the exhibition: How can books like these pose any threat to an official in Łukašenka’s system?

Their danger, of course, lies elsewhere – in their capacity to nurture empathy, invite emotional connection, and erode fear of those who are different.

According to PEN Belarus’s consolidated data, more than 80 foreign titles were officially banned in Belarus as of August 2025. Among the regime’s perceived “enemies” are authors of global stature: Anne Applebaum, James Baldwin, Fredrik Backman, Gene Sharp. What unites them? They write about dignity, freedom, and the individual’s right to choose – ideas the regime interprets not as literary themes, but as existential threats.

The authorities fear books that cultivate independent thinking, preserve historical memory, encourage doubt, and teach responsibility. Yet it is precisely these works that open a world beyond fear — a world in which freedom means participation and respect, and justice becomes a daily civic practice.

Viewed through the magnifying glass of absurdity, almost anything can be condemned. A man from Mahiloŭ shakes his head:

“Even Russian authors are treated as suspicious… Not just Suvorov — even a harmless collection of Brodsky’s poetry.”

We look into it together and discover the “reason”: a simple illustration on the cover – a tiny boat, accidentally coloured white-red-white. Someone mutters under their breath:

“They’ll latch onto anything…”

Fear has large eyes, as the saying goes – fear of reality, which relentlessly erodes the propaganda’s fabricated picture of the world.

The PEN exhibition makes this unmistakable: the rulings of ideological commissions and courts contain virtually no real argumentation — only a torrent of empty formulae. These documents read like carbon copies of the same bureaucratic template, applied indiscriminately to both documentary prose and lyrical poetry.

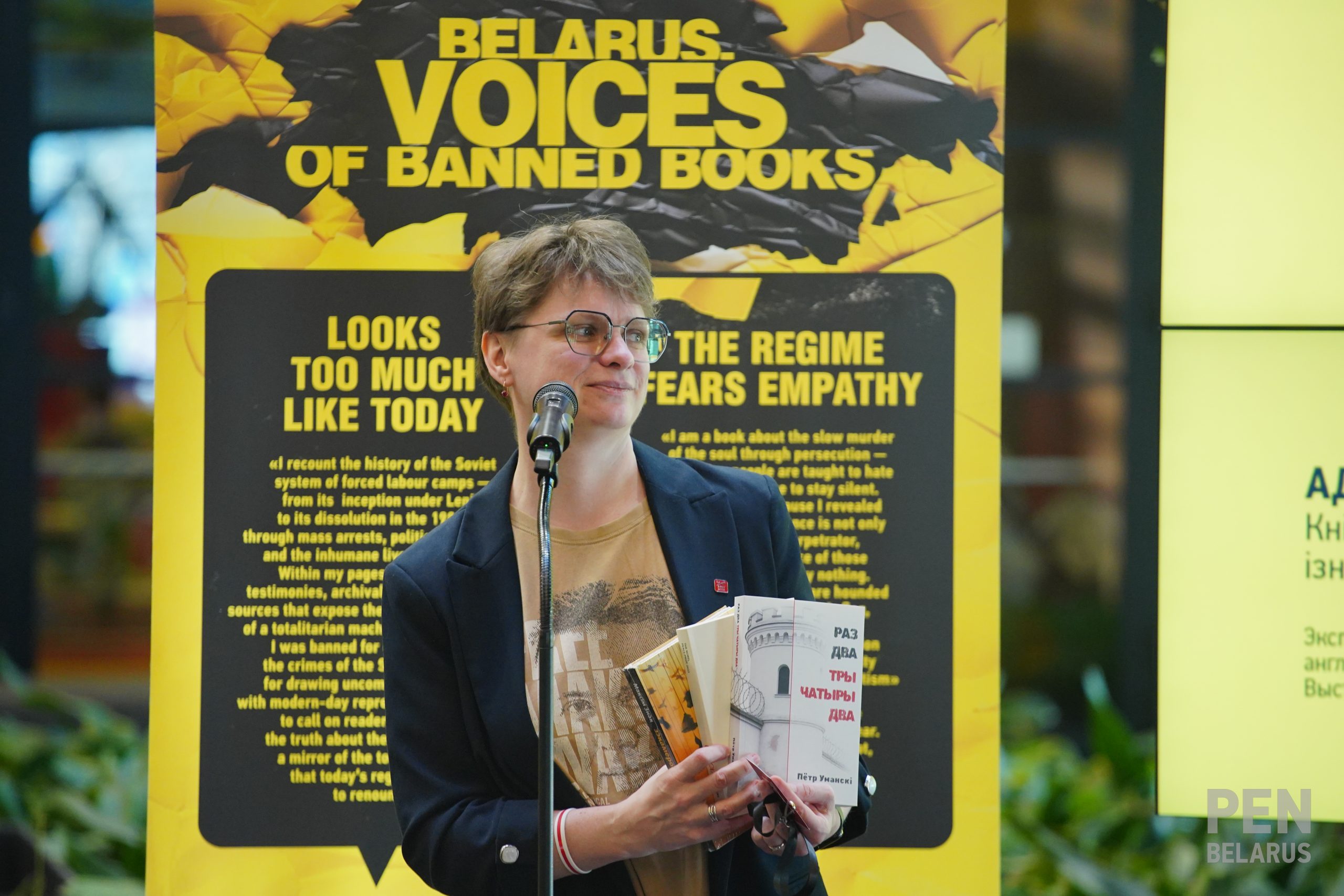

Poet and head of PEN Belarus Taciana Niadbaj captures the essence of the exhibition:

“The books gathered here differ enormously – by genre, theme, geography, and by the depth of human experience they contain. Yet they share one defining quality: a refusal to accept the worldview of a totalitarian state. They show other models of life, alternative versions of reality. Their authors place no limits on thought or emotion – and that is precisely what makes them dangerous.

Real literature does not obey power. It listens to life, catches its breath, and in doing so both reflects and shapes a new social order. It does not serve – and that, in the eyes of a dictatorship, is its unforgivable crime.”

In today’s hyper-vigilant bureaucratic optics, even our first printer, Skaryna, would be suspected of “dangerous” passages. And how many “delayed-action mines” do the ideologues detect in Kupała, Arsiennieva, Łastoŭski, Niaklajeŭ, Bacharevič, Sieviaryniec… in our classics, in living authors, in writers from abroad?

In a country where truth is treated as a threat and service to people is deemed suspicious, the words of free creators sound like defiance – grounds for prohibition. The real issue is not loyalty to the ruler, but responsibility to oneself and to Belarus.

History teaches us this: no censor has ever triumphed over the written word. A book can be burned, but its meaning cannot be destroyed. A thought can be imprisoned, but it cannot be made to disappear. This is why literature endures as the strongest form of freedom – stronger than any regime.”

More about book bans in Belarus can be found at:

https://bannedbooks.penbelarus.org

Presentation of the exhibition of banned books at the opening of the 91st PEN International Congress in Kraków, 2 September 2025

The banning of books is not only an act of censorship, but also a violation of the right to freedom of expression and access to information, as enshrined in international treaties. We document every case to ensure that the truth about cultural repression is preserved and heard.

Film premiere! Belarus. Banned Books

Specially for the exhibition, PEN Belarus has prepared a film in which we talk about the situation with banned books in Belarus and around the world, the history of such bans, and their legal consequences. We also spoke with people directly affected by this issue — authors, publishers, international experts, and human rights defenders — who shared their perspectives on the problem of book banning.

The film features: Taciana Niadbaj (PEN Belarus), Daniel I. Pedreira (PEN Cuba), Justyna Czechowska (PEN Poland), Hanna Nordell (PEN Sweden), Jennifer Finney Boylan (PEN America), Andrej Januškievič (Belarusian publisher), Jury Kozikaŭ (lawyer, PEN Belarus).

The film is available with two subtitle options: Belarusian + English, and Belarusian + Polish.

Film with Belarusian and English subtitles:

Film with Belarusian and Polish subtitles:

The film helps to shed light on what is currently happening to Belarusian books, the repression they face, and how this affects the state of Belarusian culture as a whole.